Apr 25, 2025

Behavioral Avoidance Test in virtual reality (vr-BAT) and in-vivo (real-BAT)

- Sergio Frumento1,2,

- Edoardo Magnavacca1,3,

- Alessio Iannizzotto1,2,

- Angelo Gemignani1,3,

- Enzo Pasquale Scilingo1,4,

- Danilo Menicucci1,3,

- Alberto Greco1,4

- 1University of Pisa;

- 2Department of Information Engineering, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy;

- 3Department of Surgical, Medical, Molecular and Critical Area Pathology, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy;

- 4Department of Information Engineering and Research Center "E. Piaggio", University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy

- Alberto Greco: Associate Professor;

Protocol Citation: Sergio Frumento, Edoardo Magnavacca, Alessio Iannizzotto, Angelo Gemignani, Enzo Pasquale Scilingo, Danilo Menicucci, Alberto Greco 2025. Behavioral Avoidance Test in virtual reality (vr-BAT) and in-vivo (real-BAT). protocols.io https://dx.doi.org/10.17504/protocols.io.yxmvmyom9v3p/v1

License: This is an open access protocol distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Protocol status: Working

We used this protocol and it's working

Created: March 21, 2025

Last Modified: April 25, 2025

Protocol Integer ID: 124784

Disclaimer

DISCLAIMER – FOR INFORMATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY; USE AT YOUR OWN RISK

The protocol content here is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal, medical, clinical, or safety advice, or otherwise; content added to protocols.io is not peer reviewed and may not have undergone a formal approval of any kind. Information presented in this protocol should not substitute for independent professional judgment, advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Any action you take or refrain from taking using or relying upon the information presented here is strictly at your own risk. You agree that neither the Company nor any of the authors, contributors, administrators, or anyone else associated with protocols.io, can be held responsible for your use of the information contained in or linked to this protocol or any of our Sites/Apps and Services.

Abstract

Volunteers were asked to participate in two experimental sessions separated by at least two weeks. In one session they were asked to undergo the vr-BAT, and in the other one the traditional version with a real spider (real-BAT): the order of the sessions was randomized.

During each stage of the task, volunteers – even if invited to get as close as possible to the spider – were explicitly allowed to interrupt the task whenever they would have feel that it was intolerable: in that case, in the real-BAT they had to drop a bag of coarse salt that they had to hold in the dominant hand; in the vr-BAT they had to simultaneously press the two buttons (primary button of the Meta Controller held by the participant's dominant hand) of the VR controller, which caused an immediate shutdown of the virtual scenario.

After these instructions, in the real-BAT the experimenter asked the participant to approach a real spider placed in a cage on a pedestal at the end of a corridor. Unbeknownst to volunteers, the caged spider was a taxidermy spider: however, the experimenter described it as a living one if the participant asked for details. Participants were first asked to leave the lab room and enter the corridor from a perspective that did not immediately allow to see the spider; if they agreed, they were then asked to turn by 180° (thus being able to see the pedestal at the end of the corridor) and to approach the spider as close as possible; if they reached the cage, they were asked to touch it and immediately stopped if they were actually going to do it. Of note, the beginning of the task was determined through a countdown – “one, two, three, go!” – by the experimenter: simultaneously with the command “go!”, the experimenter also started a timer to measure the completion time of the task, which was stopped when the salt bag was dropped or when the participant reached the spider’s cage.

Analogously, after the instructions, in the vr-BAT participants were asked to wear the VR headset and to hold the related controller with the dominant hand: that controller was represented in the virtual scenario as a sphere whose movements mirrored those of the real hand holding it. The task was carried out sitting on a rotating stool where the participant was instructed to rotate at the beginning of the task to turn the virtual body towards the pedestal with the spider cage on top. By moving the controller’s stick, the virtual avatar approached the cage at a maximum velocity of 0.6 m/s circa: if the participant could not tolerate the spider’s closeness, the task could be stopped by pressing the two controller’s buttons simultaneously. The approaching movement was allowed only perpendicularly to the spider’s cage, and orienting the VR controller diagonally slowed the avatar's velocity depending on the angle. Once reached a distance of 0.94 m from the spider’s cage, any further approach was impeded: the participant was then instructed to reach the cage with the sphere representing the hand. As soon as the sphere collided with the spider’s cage, the scenario was turned off and the participant exited the virtual immersion.

Safety warnings

The protocol contains images of spiders: if you are afraid of this animal, you could find some pictures disturbing.

Ethics statement

This experimental procedure was approved by the Ethical Committee of University of Pisa with protocol 0025068/2019

Preliminary steps

Preliminary steps

Filling of informed consent and questionnaires

Candidates are invited to sign the informed consent and the questionnaires used to check inclusion and exclusion criteria

Sessions organization

The selected volunteers are made able to choose a date for the first session and a date for the second one (the two dates being distanced by at least two weeks) through an online calendar

The order was randomized to administer the real-BAT first and the vr-BAT second, or viceversa.

In the list below, each of the two cases can be selected

real––>vr-BAT1 step

real-BAT in the first session

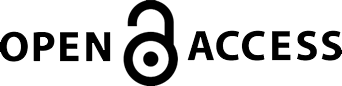

Its experimental setting (Figure 1B) consisted of a 12 x 1,80 x 3,00 m corridor located in a university hospital building, furnished with various doors – three on the sides and one at the end – that were always closed during the tasks.

At the end of the corridor, a taxidermy of a real spider (Eurypelma spinicrus; Figure 1A) was placed in a cage on a pedestal.

Each participant started in the same position (marked with a sign on the floor) facing a further door, initially giving the back to the corridor.

Figure 1

Volunteers were explicitly allowed to interrupt the task whenever they would have feel that it was intolerable: in that case, they had to drop a bag of coarse salt that they had to hold in the dominant hand.

After these instructions, the experimenter asked the participant to approach a real spider placed in a cage on a pedestal at the end of a corridor (Figure 1B). Unbeknownst to volunteers, the caged spider (Figure 1A) was a taxidermy spider: however, the experimenter described it as a living one if the participant asked for details. Participants were first asked to leave the lab room and enter the corridor from a perspective that did not immediately allow to see the spider; if they agreed, they were then asked to turn by 180° (thus being able to see the pedestal at the end of the corridor) and to approach the spider as close as possible; if they reached the cage, they were asked to touch it and immediately stopped if they were actually going to do it. Of note, the beginning of the task was determined through a countdown – “one, two, three, go!” – by the experimenter: simultaneously with the command “go!”, the experimenter also started a timer to measure the completion time of the task, which was stopped when the salt bag was dropped or when the participant reached the spider’s cage.

vr-BAT in the second session

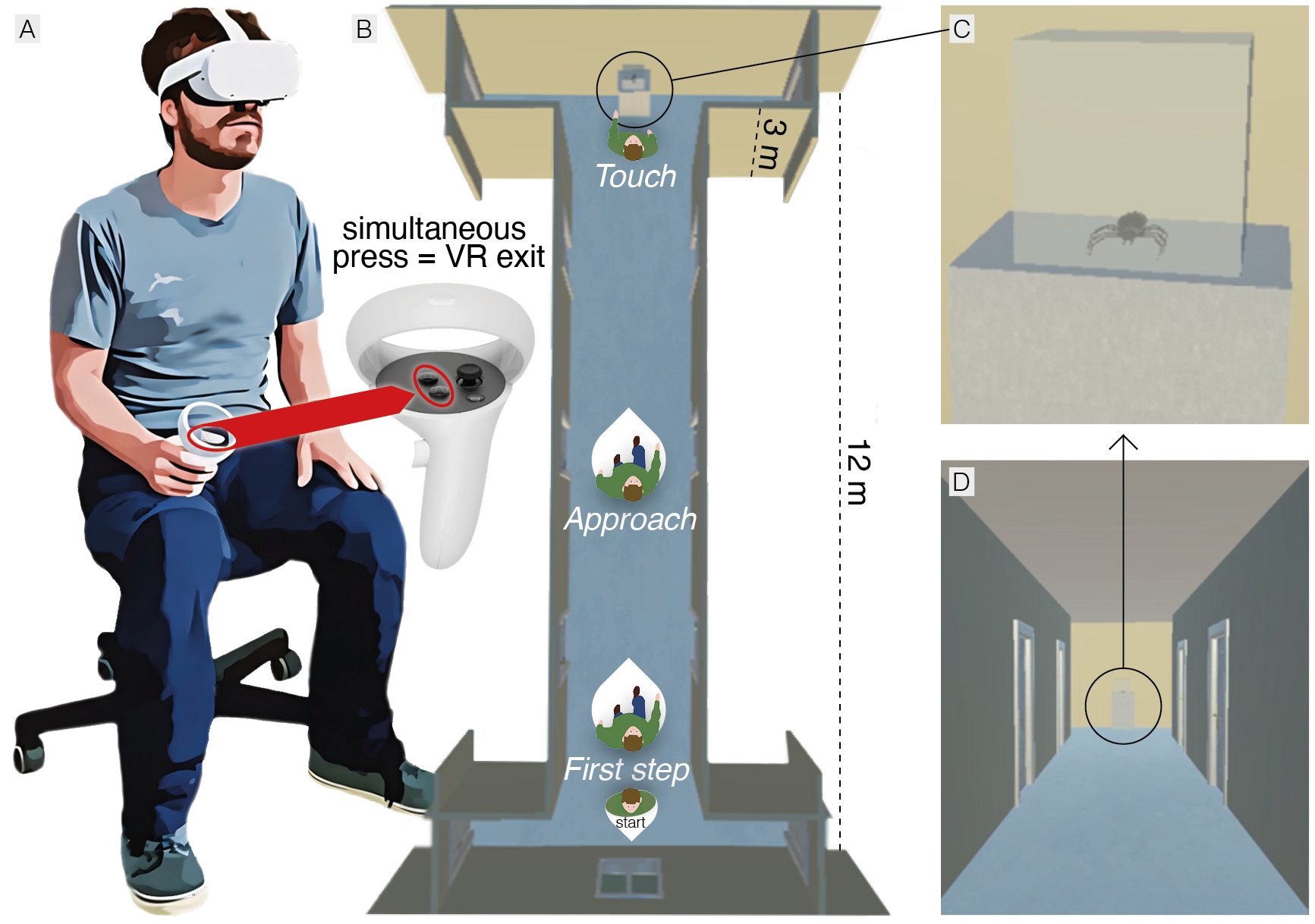

Its (virtual) experimental setting (Figure 2A) consisted of a scenario (Figure 2B) reliably reproducing the architectural properties of its real counterpart with minimal differences – same corridor of 12 x 1,80 x 3,00 m dimensions, same number and position of the doors (Figure 2D) – and using more soft-toned colors and lights.

Differently from the setting used in the real-BAT (which placed the starting point in front of a closed door), in the vr-BAT:

- the participant’s starting point was in front of a window facing a garden (bottom of Figure 2B) to avoid inducing claustrophobia;

- the spider’s cage (Figure 2C) was placed in front of a wall.

Figure 2

Volunteers were explicitly allowed to interrupt the task whenever they would have feel that it was intolerable: in that case, they had to simultaneously press the two buttons (primary button of the Meta Controller held by the participant's dominant hand) of the VR controller, which caused an immediate shutdown of the virtual scenario.

After these instructions, participants were asked to wear the VR headset and to hold the related controller with the dominant hand: that controller was represented in the virtual scenario as a sphere whose movements mirrored those of the real hand holding it. The task was carried out sitting on a rotating stool (Figure 2A) where the participant was instructed to rotate at the beginning of the task to turn the virtual body towards the pedestal with the spider cage on top (Figure 2B). By moving the controller’s stick, the virtual avatar approached the cage at a maximum velocity of 0.6 m/s circa: if the participant could not tolerate the spider’s closeness, the task could be stopped by pressing the two controller’s buttons simultaneously. The approaching movement was allowed only perpendicularly to the spider’s cage (Figure 2D), and orienting the vr controller diagonally slowed the avatar's velocity depending on the angle. Once reached a distance of 0.94 m from the spider’s cage (Figure 2C), any further approach was impeded: the participant was then instructed to reach the cage with the sphere representing the hand. As soon as the sphere collided with the spider’s cage, the scenario was turned off and the participant exited the virtual immersion.

Figure 2B summarizes the vr-BAT procedure (and, analogously, the real-BAT one), highlighting the main phases – First step, Approach, and Touch – measurable in the vr-BAT only.

real-BAT.png

604KB

vr-BAT.png

1.3MB

Participant's dismissal

Participant's dismissal

After the end of each session, the volunteer was thanked for the participation and dismissed